Mine, yours, ours

Exhibition opening

MMSU, Dolac 1/2, Rijeka

Thursday, 03.10., 20h

In the summer of 1968, in the midst of the global student uprising, recently deceased British poet Christopher Logue published his now legendary poem Know Thy Enemy in the second issue of The Black Dwarf, a newly started London underground journal. Logue’s anti-capitalist cry was printed on a poster with a large photograph of a fist with a seal ring featuring the iconic image of Che Guevara. His poster poetry reflected a moment when a pervasive revolutionary transformation of society and media was being called for.

Just a few months later, that very same fist reappeared on the cover of Omladinski tjednik (Youth Weekly), the official journal of the Zagreb socialist youth union – with insignia slightly adjusted to the local ideological context. Logue’s verses were replaced by the new journal’s motto “Radical or not at all.” Instead of Che Guevara, a stylized sickle and hammer pointed out from the seal ring towards the readers. The message, if watered down, stayed the same: the journal demand changes and thorough reforms.

Just a few months later, that very same fist reappeared on the cover of Omladinski tjednik (Youth Weekly), the official journal of the Zagreb socialist youth union – with insignia slightly adjusted to the local ideological context. Logue’s verses were replaced by the new journal’s motto “Radical or not at all.” Instead of Che Guevara, a stylized sickle and hammer pointed out from the seal ring towards the readers. The message, if watered down, stayed the same: the journal demand changes and thorough reforms.

This unusual ‘adaptation perfectly illustrates the leitmotif of the entire exhibition: the uncanny connection between the two journalist genres developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s in completely different ideological contexts.

The exhibition mainly deals with Yugoslav youth press, a common name for a range of various publications intended for the youth, and produced under the auspices of an extensive network of youth and student state organisations. Yugoslavian communists readily accepted this Soviet invention, originally devised as a part of the state propaganda apparatus, with the goal of steering the Yugoslav youth onto the righteous communist course. Along the way, they also adopted its main features. In line with the marginal position of the youth organizations that were only formally independent but in reality served as the transmission belt of the Party, the youth press remained bereft of journalistic values and was firmly placed on the margins of the media scene.

However, this exhibition is interested in the unusual transformation of the youth press that took place in the late 1960s, prompted by the reform of the youth organizations. The new self-management paradigm tried to install the Yugoslav youth as an active figure which takes responsibility for its own destiny. Acting in the unorthodox socialist environment, one that was increasingly open towards Western influence, the youth press rejected its original propagandistic tasks, turning into a relevant media, that transmitted fresh and subversive political and cultural messages.

British and American underground press of the time served as an unexpected, if not always conscious or literal, role model. Journals like The Berkeley Barb, Rat, Oz or It emerged as a reaction to the hidebound mainstream media. Sprouting from the margins of the scene and created by the very participants, they were prone to experiments in content and form, and promoted the radical leftist ideas of the 1960s student movements and the developing sex&drugs&rock’n’roll worldview.

Youth journalists acquired the underground journals through various channels and were immediately fascinated with their different messages, manner of presentation and perception of journalism. Led by a similar leftist pathos and inspired by an all-pervading revolutionary climate, they took over and adapted many of their themes and heroes. Amidst the similar conditions, insecure existence, and the rising pressure they faced, they instinctively reached for solutions that were similar in spirit to those of the underground press. All of this could be seen on several different levels.

The youth press became an organ of the local student movements that formed in Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The journals not only provided media space to the rebellious students, but organized their actions, thus coming into conflict with the regime. They promoted iconic leaders and symbols of the global student and anti-imperialistic uprisings, from Rudi Dutschke to the more controversial Black Panthers, a guerrilla organisation that was difficult to integrate with the ruling self-management doctrine. The Yippies’ manifesto, Jerry Rubin’s Do it: Scenarios for Revolution was printed everywhere as if it were some sort of a Marxist classic.

Unlike the underground press, the Yugoslav youth journals remained by and large focused on politics. The alternative hippie lifestyle attracted the youth journalists, but equally troubled them by their apolitical indifference. Likewise, with but a few exceptions, new rock culture penetrated on the pages of the youth press only after it could prove its progressive nature.

Unlike the underground press, the Yugoslav youth journals remained by and large focused on politics. The alternative hippie lifestyle attracted the youth journalists, but equally troubled them by their apolitical indifference. Likewise, with but a few exceptions, new rock culture penetrated on the pages of the youth press only after it could prove its progressive nature.

The ideal combination was found in the politicized American and British counterculture, whose pioneer works like Jeff Nuttall’s Bomb Culture or Richard Neville’s Play Power were presented to the readers in sequels. New York anarchist poet and anti-military activist, Tuli Kupferberg, who would later ironically call for a slaughter of students in Dušan Makavejev’s W.R. Mysteries of the Organism, appeared for the first time in the Yugoslavian context on the pages of the youth press.

Youth journals advocated sexual freedom, at times seen as an integral part of political emancipation. Their sexual revolution, like the American prototype, was marked with male sexism and rarely reached beyond the de-tabooization of the sexual act and jargon.

Finally, the youth press turned into a platform for visual experiments, in line with the underground aesthetics. Graphic editors turned the existing technical limitations to their advantage, deconstructing the usual visual patterns. Mihajlo Arsovski and Kostja Gatnik, each in their own way, introduced the psychedelic spirit and the flower-power aesthetics to a socialist environment through their unusual use of typography and fluorescent ink in Pop-Express and Tribuna. In Belgrade, Slobodan Mašić created recognizable visual identity of Susret. Florian Hajdu, assisted by the notorious film director Lazar Stojanović, experimented with form, changing the format of Vidici from one issue to the other.

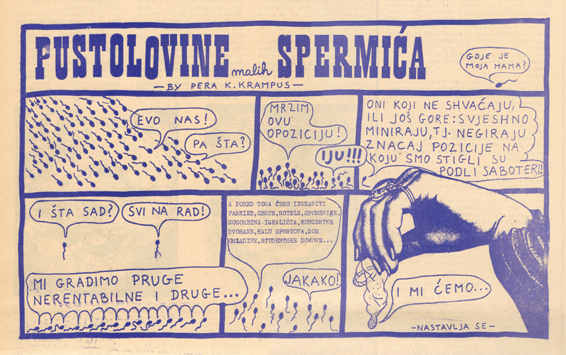

Just like the underground press, the youth press was a birthplace of alternative comics. It is here where one could see first translations of classics like Robert Crumb, but also original works of local authors such as Pero Kvesić, Bálint Szombathy and the aforementioned Kostja Gatnik alias Magna Purga.

This new underground policy of the journals did not go unnoticed by the regime. The journals’ editorial offices faced increasing pressure from the authorities, which frequently culminated in the forceful removal of the editors. Political repression in Yugoslavia in the early 1970s stroke a severe blow to the youth press that would not recover until the end of the decade.

Production of the exhibition: Galerija Galženica (http://www.galerijagalzenica.info) and Drugo more

Partners: Galerija Galženica, Savez udruga Klubtura, Museum of Modern and Contemporary art Rijeka

Curator: Marko Zubak

Programme is supported by:

Kultura Nova Foundation, European Cultural Foundation, Ministry of Culture of the Republic Croatia, Department of Culture of the City of Rijeka, Croatian Audiovisual Centre, Primorsko-goranska County

The programme is part of the international project Revisiting Footnotes and is organized in cooperation with the cultural platform IZOLYATSIA, Donetsk (Ukraine), Centre for contemporary art KSA:K, Kishinev (Republic of Moldova) and Latvian centre for contemporary art LCCA, Riga.